The Reality Behind Blockchain TPS Claims: Why Theoretical Numbers Don't Match Performance

Blockchain networks tout impressive transaction-per-second capabilities, yet these metrics rarely account for the growing strain placed on distributed nodes that maintain network decentralization.

When evaluating blockchain networks, transactions per second (TPS) metrics are commonly used as a benchmark for performance capabilities, yet these figures frequently fail to capture whether a network possesses genuine scalability when deployed in real-world conditions.

In a conversation with Cointelegraph, Carter Feldman, who founded Psy Protocol and previously worked as a hacker, explained that TPS measurements frequently paint a deceptive picture because they overlook the actual mechanics of how transactions get verified and distributed throughout decentralized networks.

"Numerous pre-mainnet, testnet or isolated benchmarking evaluations calculate TPS using just a single node in operation. When testing is conducted this way, you could just as easily describe Instagram as a blockchain capable of achieving 1 billion TPS since it operates with one centralized authority validating every API call," Feldman explained.

The problem stems partly from the fundamental architecture of most blockchain systems. As these networks attempt to increase speed, every individual node experiences heavier loads, which in turn makes maintaining decentralization increasingly challenging. This operational burden can be mitigated by creating a separation between the execution of transactions and their verification processes.

The decentralization tax that TPS metrics overlook

As a measurement of blockchain capabilities, TPS serves as a legitimate performance indicator. When a network demonstrates higher TPS capacity, it possesses the ability to accommodate greater levels of actual usage.

However, Feldman contended that the majority of widely publicized TPS statistics reflect optimal testing environments that fail to correspond with actual real-world throughput capabilities. These eye-catching numbers conceal how the system actually behaves when operating under genuinely decentralized circumstances.

"The TPS achieved by a virtual machine or an individual node doesn't constitute a genuine measurement of a blockchain's actual mainnet performance," Feldman stated.

"However, the number of transactions per second a blockchain can process in a production environment is still a valid way to quantify how much usage it can handle, which is what scaling should mean."

Within a blockchain network, every full node must verify that transactions comply with the protocol's established rules. When one node validates an invalid transaction, other nodes in the network should reject it. This verification process forms the foundation of how a decentralized ledger functions.

When evaluating blockchain performance, the focus often centers on how quickly a virtual machine can execute transactions. In practical deployment scenarios, however, factors like bandwidth availability, latency issues and network topology configuration become critically important. Consequently, actual performance depends heavily on how transactions get received and verified across the distributed network of nodes.

This reality explains why TPS numbers promoted in white papers frequently deviate significantly from actual mainnet performance. When benchmarks separate execution processes from the costs associated with relay and verification, they're measuring something that more closely resembles virtual machine speed rather than true blockchain scalability.

EOS, a blockchain network where Feldman previously served as a block producer, shattered initial coin offering records during 2018. The project's white paper indicated a theoretical capacity approaching approximately 1 million TPS. Even when measured against 2026 standards, this represents a remarkably impressive figure.

The EOS network never achieved its theoretical TPS objective. Earlier assessments suggested it could achieve 4,000 transactions when operating under favorable conditions. Yet research performed by blockchain testing specialists at Whiteblock revealed that when subjected to realistic network conditions, actual throughput dropped to approximately 50 TPS.

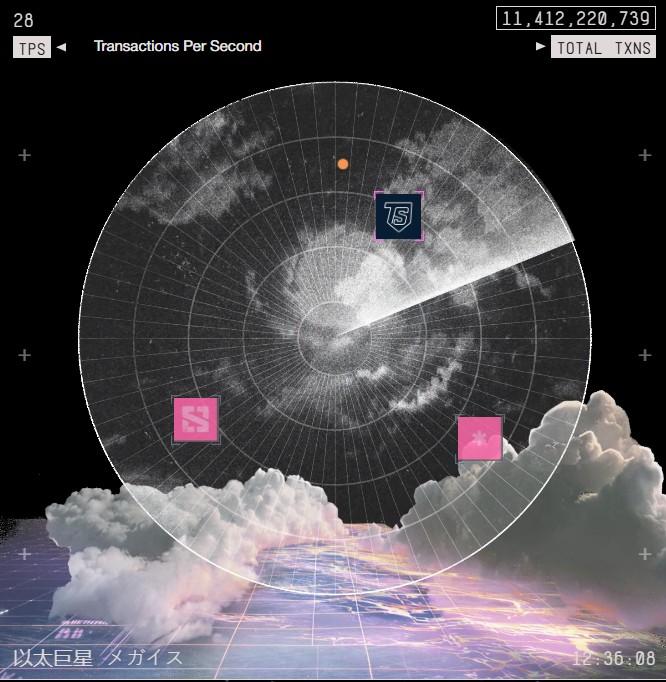

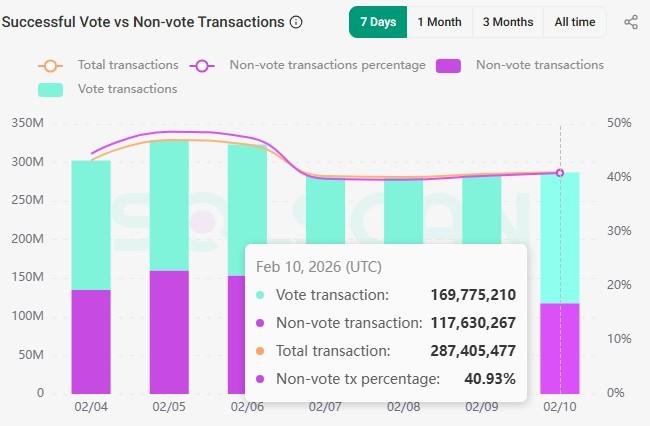

During 2023, Jump Crypto showcased that its Solana validator client, Firedancer, accomplished what EOS couldn't by demonstrating 1 million TPS in testing. Since that demonstration, the client has been progressively deployed, with numerous validators now operating a hybrid implementation called Frankendancer. In current live operational conditions, Solana typically handles approximately 3,000-4,000 TPS. Around 40% of these transactions represent non-vote transactions, which serve as a better indicator of genuine user activity.

Solving the linear scaling challenge

In most blockchain systems, throughput capacity scales in a linear relationship with workload demands. While more transactions indicate increased network activity, it simultaneously means that nodes must receive and verify larger volumes of data.

Every individual transaction contributes additional computational demands to the system. Eventually, limitations imposed by bandwidth capacity, hardware specifications and synchronization delays render further scaling increases unsustainable unless decentralization is compromised.

According to Feldman, overcoming this fundamental constraint demands reimagining the approach to proving validity, which can be accomplished through zero-knowledge (ZK) technology. ZK represents a cryptographic method for proving that a collection of transactions underwent correct processing without requiring every node to re-execute those transactions. Since this technology enables validity to be proven while keeping underlying data concealed, ZK is frequently promoted as an answer to privacy concerns.

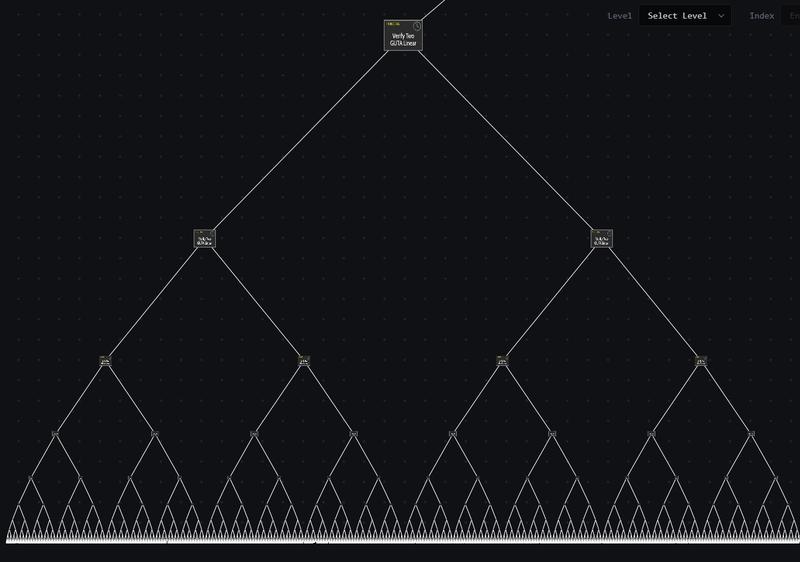

Feldman maintains that it also offers a solution to the scaling challenge through recursive ZK-proofs. Explained simply, this concept refers to proofs that verify the validity of other proofs.

"What we've discovered is that you can combine two ZK-proofs and generate a ZK-proof that proves that both of these proofs are correct," Feldman said. "So, you can take two proofs and make them into one proof."

"Let's say we start with 16 users' transactions. We can take those 16 and make them into eight proofs, then we can take the eight proofs and make them into four proofs," Feldman explained while sharing a graphic of a proof tree where multiple proofs ultimately become one.

Traditional blockchain architecture dictates that raising TPS increases both verification requirements and bandwidth demands for every participating node. According to Feldman's argument, with a proof-based architectural design, throughput capacity can be expanded without creating a proportional increase in per-node verification costs.

This doesn't suggest that ZK technology completely removes all scaling tradeoffs. The process of generating proofs can be computationally demanding and may necessitate specialized infrastructure. Though verification becomes inexpensive for standard nodes, the computational burden transfers to provers who must execute intensive cryptographic operations. Additionally, integrating proof-based verification into existing blockchain architectures presents significant complexity, which partially explains why the majority of major networks continue utilizing traditional execution models.

Evaluating performance beyond simple throughput metrics

TPS isn't without value, but its usefulness comes with conditions. In Feldman's view, raw throughput statistics carry less significance than economic indicators such as transaction fees, which offer a more accurate representation of network health and user demand.

"I would contend that TPS is the number two benchmark of a blockchain's performance, but only if it is measured in a production environment or in an environment where transactions are not just processed but also relayed and verified by other nodes," he said.

The dominant design paradigm of existing blockchains has also shaped investment patterns. Networks built around sequential execution models cannot easily integrate proof-based verification without fundamentally redesigning their transaction processing mechanisms.

"In the very beginning, it was almost impossible to raise money for anything but a ZK EVM [Ethereum Virtual Machine]," Feldman said, explaining Psy Protocol's former funding issues.

"The reason people didn't want to fund it in the beginning is that it took a while," he added. "You can't just fork EVMs or their state storage because everything is done completely differently."

Across most blockchain networks, elevated TPS translates into increased work for every participating node. A headline figure by itself fails to reveal whether that workload level is sustainable over time.