Combating Frontrunning Through Per-Transaction Encryption: The Flash Freezing Flash Boys Approach

An innovative approach to preventing frontrunning attacks, Flash Freezing Flash Boys introduces per-transaction encryption mechanisms for blockchain security.

Ethereum traders face considerable danger from malicious MEV attacks. Recent research we've conducted reveals that sandwich attacks occur nearly 2,000 times per day, with monthly extraction from the network exceeding $2 million. Traders remain vulnerable even when conducting substantial swaps involving WETH, WBTC, or stablecoins, potentially losing significant portions of their transaction value.

The transparent characteristics of blockchain networks enable MEV to flourish, as transaction information becomes visible prior to execution and finalization. Mempool encryption represents one viable avenue for MEV mitigation, especially when utilizing threshold encryption techniques. Our previous analyses explored two distinct approaches to threshold-encrypted mempools. Among the pioneering projects implementing threshold encryption for mempool protection, Shutter employed a per-epoch configuration. A more recent framework, batched threshold encryption (BTE), utilizes a single decryption key for multiple transactions, thereby decreasing communication expenses and enhancing throughput.

This analysis examines Flash Freezing Flash Boys (F3B), authored by H. Zhang et al. (2022), representing a fresh threshold encryption architecture that encrypts each transaction individually. We dissect its operational mechanisms, clarify its scalability characteristics regarding latency and memory consumption, and examine why practical deployment has not yet occurred.

The mechanics of per-transaction encryption in Flash Freezing Flash Boys

Flash Freezing Flash Boys overcomes shortcomings found in earlier threshold encryption frameworks that depended on per-epoch configurations. Systems like FairBlock and initial Shutter implementations employed a singular key for encrypting all transactions within a designated epoch. On Ethereum, an epoch represents a predetermined block count, such as 32 blocks. This approach introduced a weakness wherein certain transactions failing inclusion within specified block boundaries would nonetheless undergo decryption alongside the entire batch. Such exposure of sensitive information would create MEV exploitation opportunities for validators, rendering them susceptible to front-running attacks.

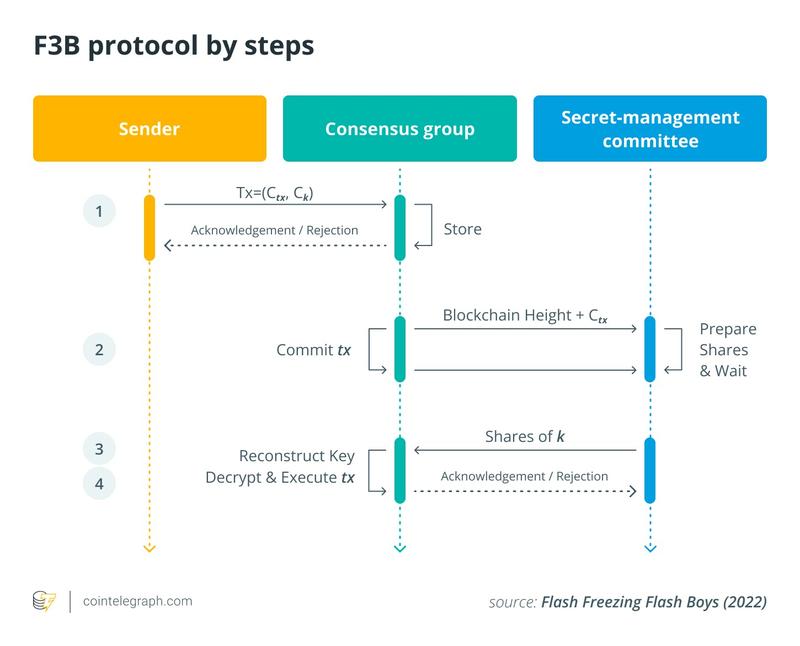

F3B implements threshold encryption at the individual transaction level, guaranteeing that each transaction maintains confidentiality until achieving finality. The diagram below illustrates the general operational flow of the F3B protocol. Users encrypt their transactions using a key accessible exclusively to the designated threshold committee, called the Secret Management Committee (SMC). Both the transaction ciphertext and encrypted key are transmitted as a paired unit to the consensus group (Step 1). This mechanism enables nodes to store and sequence transactions while retaining all necessary decryption metadata for rapid post-finality reconstruction and execution. Concurrently, the SMC generates its decryption shares but retains them until consensus commits the transaction (Step 2). Upon transaction finalization and SMC release of sufficient valid shares (Step 3), the consensus group performs decryption and executes the transaction (Step 4).

Individual transaction encryption had historically proven unfeasible given the substantial computational demands for both encryption and decryption operations, alongside storage requirements stemming from large encrypted payloads. F3B resolves this challenge by applying threshold encryption exclusively to a compact symmetric key rather than the complete transaction. The actual transaction undergoes encryption utilizing this symmetric key. This methodology can decrease the volume of data requiring asymmetric encryption by approximately ~10 times when processing a basic swap transaction.

Latency overhead and cryptographic implementation variations of F3B

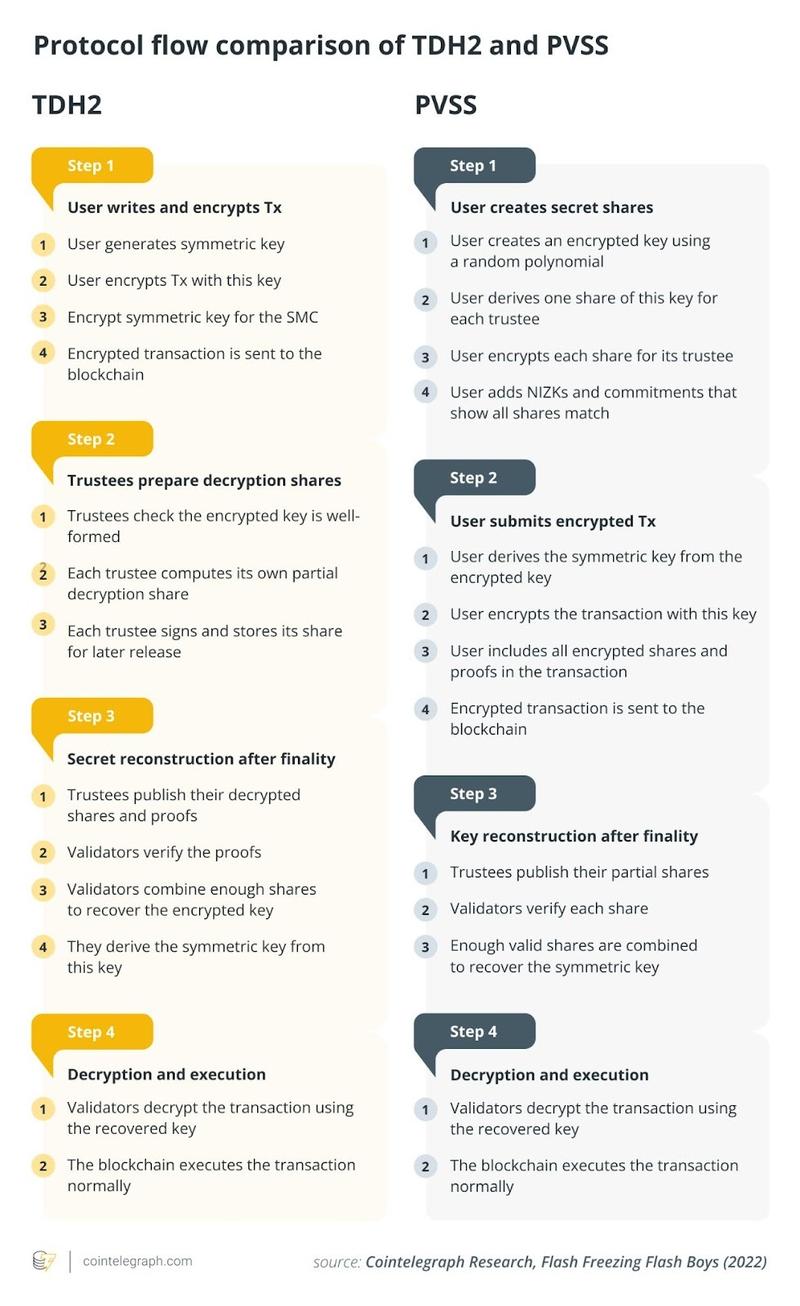

Flash Freezing Flash Boys supports implementation through two distinct cryptographic protocols: TDH2 or PVSS. The distinction centers on which party assumes the setup responsibility and the frequency of committee structure fixation, yielding respective benefits and drawbacks concerning flexibility, latency, and storage overhead.

TDH2 (Threshold Diffie-Hellman 2) depends on a committee executing a distributed key generation (DKG) procedure to generate individual key shares alongside a collective public key. Subsequently, users generate a new symmetric key, encrypt their transaction with it, and encrypt that symmetric key using the committee's public key. The consensus group records this encrypted pair on the blockchain. Following the chain's achievement of the requisite confirmation count, committee members broadcast partial decryptions of the encrypted symmetric key accompanied by NIZK (Non-Interactive Zero-Knowledge) proofs, essential for preventing chosen-ciphertext attacks, where adversaries submit corrupted ciphertexts attempting to deceive trustees into revealing information during decryption. NIZKs ensure the user's ciphertext maintains proper formation and decryptability, while also verifying trustees submitted accurate decryption shares. Consensus validates the proofs and, upon achieving a threshold of legitimate shares, reconstructs and decrypts the symmetric key, decrypts the transaction, then proceeds with execution.

The alternative scheme, PVSS (Publicly Verifiable Secret Sharing), takes a divergent approach. Rather than having the committee execute a DKG during each epoch, committee members maintain long-term private keys with corresponding public keys stored on the blockchain and available to all users. For individual transactions, users select a random polynomial and employ Shamir's secret sharing for generating secret shares, subsequently encrypted for each selected trustee utilizing their respective public key. The symmetric key derives from hashing the reconstructed secret. Each encrypted share includes an accompanying NIZK proof, enabling anyone to confirm that all shares originated from an identical secret, together with a public polynomial commitment, a record establishing the share-secret relationship. The following steps involving transaction inclusion, post-finality share release, key reconstruction, decryption and execution mirror those in the TDH2 scheme.

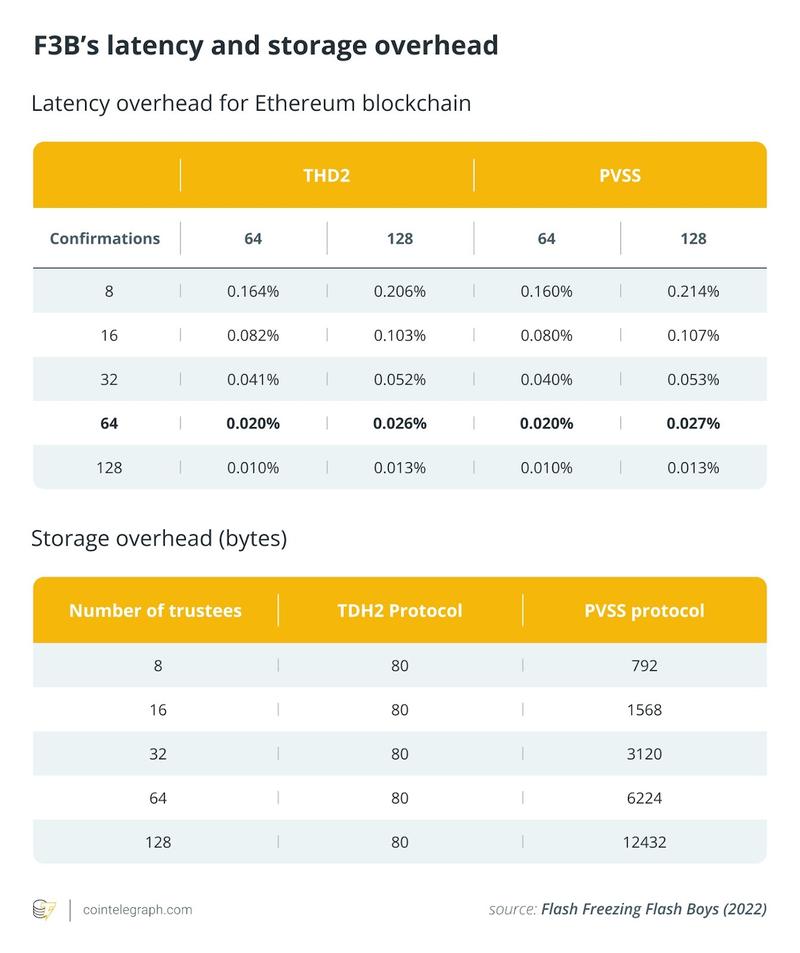

The TDH2 protocol demonstrates superior efficiency through its fixed committee structure and constant-size threshold-encryption data. PVSS, conversely, provides users with enhanced flexibility, permitting them to designate which committee members handle their transaction. Nevertheless, this advantage comes with the trade-off of expanded public-key ciphertexts and elevated computational overhead resulting from per-trustee encryption. Examining the broader context, the prototype implementation of the F3B protocol on simulated proof-of-stake Ethereum demonstrated minimal performance impact. Using a committee comprising 128 trustees, the post-finality delay measures merely 197 ms for TDH2 and 205 ms for PVSS, representing 0.026% and 0.027% of Ethereum's 768-second finality duration. Storage overhead amounts to just 80 bytes per transaction for TDH2, whereas PVSS's overhead expands linearly relative to trustee count owing to per-member shares, proofs and commitments. These findings validate that F3B could provide its privacy assurances with negligible effects on Ethereum's performance and capacity.

The reward and penalty system within Flash Freezing Flash Boys

F3B promotes honest conduct among Secret Management Committee trustees via a staking framework featuring locked collateral. Transaction fees provide trustees with motivation to remain online and sustain the performance standards the protocol demands. A slashing smart contract guarantees that upon submission of violation proof, demonstrating premature decryption execution, the violating trustee forfeits their stake. Within TDH2, such evidence comprises a trustee's decryption share subject to public verification against the transaction ciphertext. In PVSS, the evidence consists of a decrypted share alongside a trustee-specific NIZK proof authenticating it. This framework penalizes demonstrable premature disclosure of decryption shares, raising the expense of detectable misconduct. However, it cannot prevent trustees from engaging in private off-chain collusion to reconstruct and decrypt transaction data without publishing any shares. Consequently, the protocol continues to depend on the presumption that the majority of committee members maintain honest behavior.

Given that encrypted transactions cannot undergo immediate execution, an additional vulnerability exists where malicious users could inundate the blockchain with non-executable transactions to degrade confirmation times. This represents a potential attack surface shared by all encrypted mempool schemes. F3B mandates that users provide a storage deposit for each encrypted transaction, rendering spamming economically prohibitive. The system deducts the deposit initially and refunds only a portion upon successful transaction execution.

Implementation obstacles for F3B on Ethereum

Flash Freezing Flash Boys presents a thorough cryptographic strategy for MEV mitigation, yet practical deployment on Ethereum appears unlikely given the integration complexity involved. While F3B maintains the consensus mechanism intact and preserves complete compatibility with current smart contracts, it necessitates modifications to the execution layer for supporting encrypted transactions and delayed execution. This would demand a considerably more extensive hard fork than any other upgrade implemented since The Merge.

Nonetheless, F3B constitutes a significant research achievement extending beyond Ethereum's boundaries. Its trust-minimized framework for sharing confidential transaction data applies to both emerging blockchain networks and decentralized applications requiring delayed execution. F3B-style protocols offer utility even on sub-second blockchains where reduced block times already substantially diminish MEV, to comprehensively eliminate mempool-based front-running. As a practical application example, F3B could function within a sealed-bid auction smart contract, where participants submit encrypted bids remaining concealed until the bidding phase concludes. Consequently, bids undergo revelation and execution exclusively following the auction deadline, preventing bid manipulation, front-running or premature information disclosure.